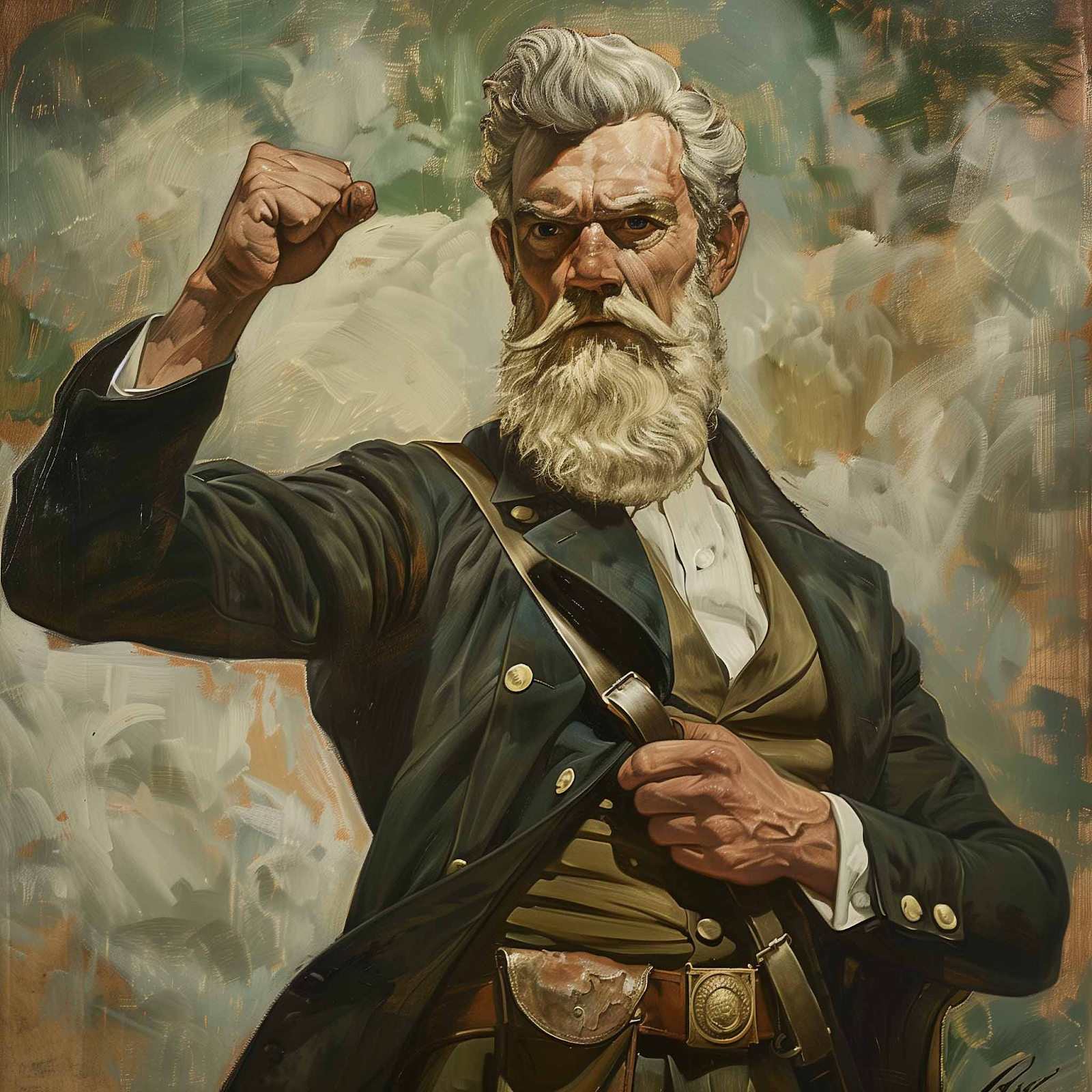

Although there are many prevalent names throughout history, few have stirred up as much controversy as my own, John Brown. I was born in the spring of 1800 as the fourth child of Ruth Mills and Owen Brown, both of whom were strict Calvinists. Consequently, my parents ardently despised slavery, claiming that the institution of slavery juxtaposed the beneficent will of God. As I grew up in the small town of Torrington, Connecticut, these values were imposed upon me and I began to share their disdain for slavery. This sentiment was reinforced in Michigan during a cattle drive when I was twelve years old.

Towards the completion of my journey, I was fortunate enough to encounter the hospitality of a farmer who provided me with food and a lodge. Despite my young age, he treated me with respect and dignity; however, the farmer's slave did not receive the same level of regard. Right before my eyes, the farmer violently hammered the enslaved boy with a metal shovel, a memory I could never forget; such an event furthered my hatred for slavery and inspired an ardent desire to bring an end to the evil institution.

However, my abolitionist aspirations were incompatible with my youth, so I left my native state of Ohio and pursued ministry in Massachusetts. There, I studied under Reverend Hallock until I developed an unexplained case of Uveitis, leading to the early termination of my studies. As a result, I was forced to make a premature return to Ohio. This unexpected happening altered the course of my life; perhaps, with the completion of ministry school, I would have lived a peaceful life, propagating the word of my Lord and Savior. Instead, I remained in Ohio and married the lovely Dianthe Lusk who would become the mother of my many children in 1820. Over the next two decades, I frequently traveled to pursue business ventures, including speculation and tanning. Unfortunately, my enterprise never led to financial success and I had to file for bankruptcy in the 1840s.

Even still, I found ways to contribute to the abolitionist cause. Among other supportive actions, I donated funds in support of activists, such as David Walker and Henry Highland. At the same time, the second great revival precipitated a religious fever that further opened my eyes to the unpalatable truth: slavery was incompatible with God's kingdom and required immediate elimination. Soon after this revelation, I began my crusade against slavery as a conductor in the Underground Railroad. During my time with the railroad, I established the League of Gileadites which aspired to provide assistance and protection to escaped slaves. Through the aforementioned organization, I hoped to reduce the number of freedmen who fell back into the evil clutches of slavery.

Years later, the Kansas-Nebraska Act would send the nation into turmoil. Proposed by Stephan A. Douglas, the legislation asserted that the legality of slavery in Kansas and Nebraska was to be determined by the popular sentiment held by the citizens of the particular state, a concept known as popular sovereignty. Unwilling to allow the sinful institution of slavery to expand any further than it already had, I collected my belongings and headed west with five of my sons to the Kansas territory. There, I took an active role in the fight against slavery, becoming involved with a paramilitary group known as the Pottawatomie Company.

Not long after my arrival Lawrence, the capital of the anti-slavery movement, was looted and burned by pro-slavery settlers on May 21st, 1856. Immediately after I received news about the sacking of Lawrence, I resolved to carry out my revenge against the anti-abolitionists in Kansas. A few days later on May 24th, I traveled to several pro-slavery residences as the judge, jury, and executioner; with the help of five my sons and James Townsly, I dragged five slave owners from their homes and killed them in cold blood, freeing a total of eighteen slaves. This massacre in Pottawatomie sent a shockwave of fear and panic through the entire country, precipitating an outbreak of unorganized violence, a period known as "bleeding Kansas."

Before long, I became controversial in American politics due to my unprecedented violence. Some supported my cause while others condoned my actions. Nonetheless, I continued to carry on the fight against slavery in the Battle of Black Jack and the Battle of Osawatomie. Unsatisfied with my progress, I withdrew from the front line and began scheming an attack on the establishment of slavery that I believed would undoubtedly lead to its eradication. My strategy for liberation involved a seizure of the Harper's Ferry armory and was contingent on the assumption that enslaved Americans would join my cause.

On October 16th, 1859, I would set my fateful plan into motion around eight o'clock in the evening. Although the raid on Harper's Ferry proceeded as expected during the early hours, it quickly began to fall apart; the nearby slaves never committed their efforts, and the citizens of West Virginia resisted my advances vehemently. By the midnight of the next day, my attack had been thwarted by the misplaced talents of General Robert E. Lee, leading to my arrest.

Immediately after being taken into custody, I was tried for murder, incitement, and treason against the State of Virginia. As I stood before the court, sure of my fate, I passionately exclaimed, " I have done, . . . in behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong, but right!" With abounding enthusiasm, I continued, "if it be deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children, and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit: so let it be done!" After only forty-five minutes of deliberation, the court decided I was to be hung on December 2, 1859. As I reflected on my life during the final moments, I found no regret; I was a man of God fighting for His cause as I understood it. In the end, my actions were in accordance with the biblical proposition that all men were created equal. As I walked up the steps of the gallows, I handed the jailor a note that read, "I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done."

Although I failed to abolish slavery, my attempted insurrections terrified white Southerners, cultivating a belief that the issue of slavery could not be remedied. Slave owners associated my name with terrorism and reasoned that it was unsafe to remain a part of the United States, a logic that led to secession on December 20th, 1860. Conversely, abolitionists perceived my actions as those of a martyr. Notably, the Union soldiers crafted a song in memorandum of my legacy by the name of John Brown's Body which gained widespread popularity during the Civil War. In all, my dedication to the abolitionist cause undeniably shaped American history. However, my actions are perceived, their mark on history cannot be erased.